Crime is contagious. Of that, there is little doubt. A central predictor of crime levels in a neighborhood is how much crime there is in the neighborhood next door. Communities that share borders share crime (technically, this is known as spatial autocorrelation).

Over the past few decades, criminologists have become convinced that places can make people more crime-prone than they otherwise would be. Fix the place, and the people will be safer. For instance, a place with lots of alcohol outlets will almost certainly have more violence than an otherwise identical place with few places to buy liquor.

The best analogy is the spread of a virus. Each individual exposed to a virus has some chance of getting sick, but those with weaker immune systems have a greater risk of falling ill. Places bear similar risks. Certain features--poverty, density, isolation--put people in those places at greater risk of victimization.

A thought experiment can show how this works. Suppose we set up the worst-case scenario, one where cities have no recourse to reduce crime other than arranging where people live. And suppose a city was assigned a set number of high-risk (economically disadvantaged) places, a set number of low-risk (highly prosperous) places, and some in between. Now we ask, how should the city arrange those places to create the most safety and the least amount of crime?

The answer is surprising. While we know that isolating our poorest residents is really bad for them, it turns out that segregating the rich and poor leads to the worst outcomes for a city as a whole. Economic integration, where the rich and poor live side by side, leads to the safest cities.

To test this hypothesis, I have borrowed some Brookings Institution models describing the spread of viruses. Working with our DC Crime Policy Institute, the Brookings scholars determined that at least 70 percent of crime in Washington, DC, is due to contagion (the spreading of crime like an epidemic).

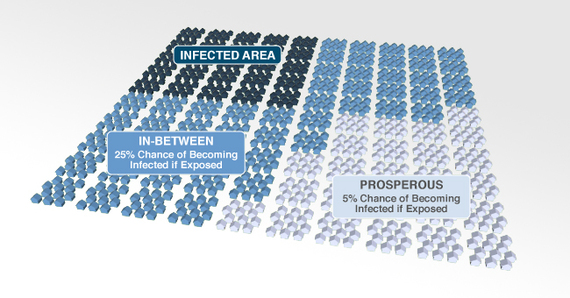

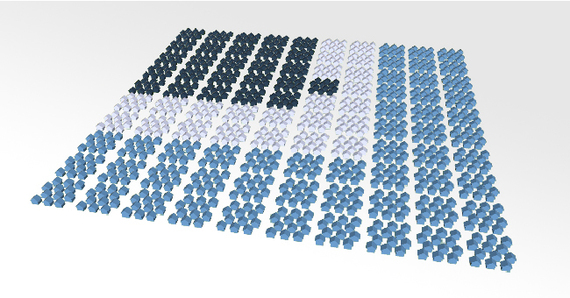

How does that work? Below, I describe a city as a 10 X 10 grid. Each of the 100 cells in the grid is a neighborhood. The neighborhoods have some intrinsic ability to fight a crime infection. The dark shaded areas are the most isolated, poorest, densest neighborhoods--and for this very stylized model, I assume they are all infected with the crime bug. The in-between areas (the lightly shaded areas) have a 25 percent chance of becoming infected if they are "exposed" to a neighboring community with high crime. The prosperous neighborhoods (the unshaded areas) are far more resilient; they only have a 5 percent chance of being infected if exposed.

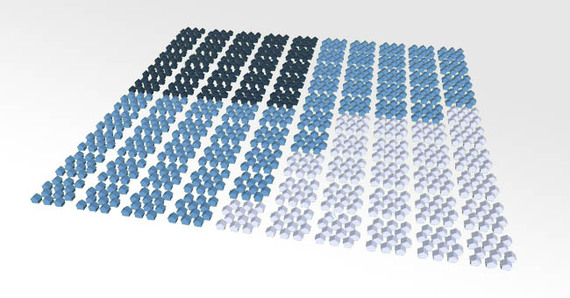

First, let's consider a perfectly segregated city. All the high-crime neighborhoods are in the same part of the city. All the prosperous places are physically isolated from the high-crime places by the in-between neighborhoods.

When you work through the entire epidemic, you find that the 25 infected neighborhoods infect an additional 17 neighborhoods. By segregating and isolating the most at-risk places, crime is not corralled, but rather spreads more effectively.

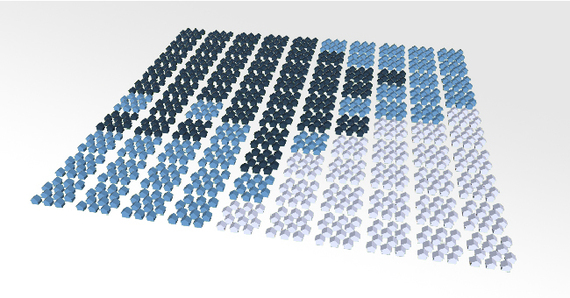

Now imagine that instead of surrounding the infected places with in-between places, we instead surround the infected places with the most prosperous places.

Since only 1 in 20 (5 percent) prosperous places is infected when exposed to the crime virus, then only one prosperous neighborhood is infected in this thought experiment.

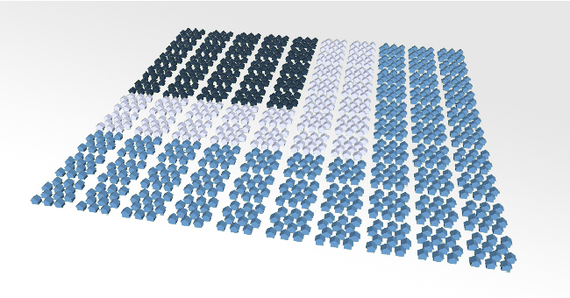

Thus, having rich and poor live side by side means 26 of our 100 neighborhoods have crime problems. That is a vast improvement to absolute segregation, where 42 of our 100 neighborhoods are infected. (You can read the entire thought experiment here or here ).

Of course, this thought experiment ignores the positive benefits of vaccinating places. Cities have many potential vaccines in their arsenal to prevent the spread of a crime epidemic. Identifying which vaccines are most effective is at the core of the discussion about which elements of city life are most important in preventing crime. And, as Richard Florida points out, these elements need not directly pertain to crime fighting. But it is helpful to begin that discussion by framing it in terms of contagion, epidemics, and vaccines.

The bottom line is, just as we cannot arrest our way out of crime problems, we also cannot economically segregate and isolate our way out either. That approach is self-destructive and has led to many of the problems our cities face today. Figuring out how to fix those mistakes is at the core of creating prosperous places.